One thing I occasionally do is a sort of third-person-post-mortem of a game I’ve been playing a lot of. I think about how it might have been put together from a game design and programming perspective. Of course this sort of analysis is just my opinion, but I do try to think things through far enough to prove my point. Often I go so far as to recreate the core game mechanic as a rapid prototype, just to be sure that my thinking is correct.

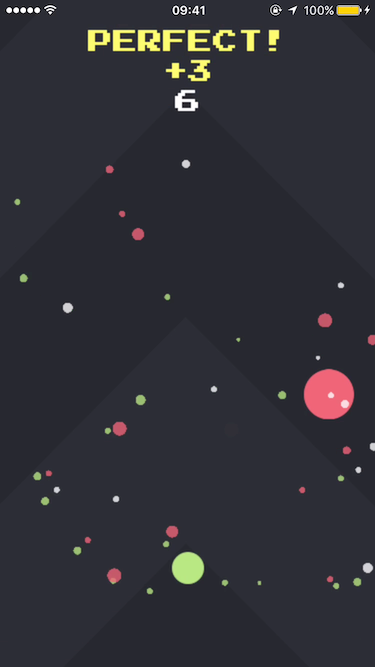

Boom Dots by Umbrella Games is a great minimalist, arcade-style game that has enjoyed continued success on the App Store. What struck me about the game—other than how well it has been put together — was how simple and elegant the concept is. I see it as a simplified version of Space Invaders. The developer has sucessfully reduced an already simple concept to its bare essentials, doing away with both player movement and enemy formation in the process. You might think that removing those two keys elements would remove the fun, but you’d be wrong. I think it actually amplifies the fun!

Anyway, I was playing Boom Dots, marvelling at the elegance of the concept and wishing I’d come up with it first, and I began to think about how it might be put together. That’s either a blessing or a curse, but I can’t help but think about games in that way after they get a hold of me. Boom Dots is a great game with which to start this occasional series of posts, as it’s a very simple mechanic.

There’s an Enemy Dot. And there’s a Player Dot.

The Player Dot can be released at which point it will move upwards. Meanwhile the Enemy Dot is moving back and forth across the screen.

If the Dots collide, you score and a new Enemy Dot appears. If you miss, it’s Game Over.

Testing whether the two dots, or circles, overlap is as easy as testing whether the distance between their centre points is less than the sum of their respective radiuses. A little bit of trigonometry is required. Easy.

Tapping the Player Dot gives it some velocity to it, and sends it on its way. Super easy.

Now to the Enemy Dot. The way this comes on the screen is really nice: such a smooth curve! And the way it moves back and forth: so smooth! Surely this is difficult to replicate? Well, yes, if you’re doing it from scratch. But absolutely not if you have the ability to perform tweening animations, which I tend to do using a set of tried and tested Easing functions.

Easing functions allow you to specify a curve that the speed of the animation should follow on its way from the start value to the end value. Normally it would move at a constant speed from start to end: Linear. But by adjusting the how fast we go using a mathematical formula, we can make the animation play at a different speeds depending on how far along between we are.

Perfect.

Types of curves that can be applied in this way are: Quadratic, Cubic, Quartic, Quintic, Sinusoidal, Exponential and Circular. Then there’s even Elastic and Bounce, which add a bit of wobble to proceedings.

Easings are easier to understand by looking at interactive visualisations.

So, back to the Enemy Dot moving side to side. We want the animation to start slowly, speed up, then slow down. Looking at the visualisations we see that easeInOutSine will do that, and it’s not as severe as some of the others so it’d be a good one to try first. By applying the easeInOutSine Easing function to the Enemy Dot as it travels back and forth we can get just the effect we require. We can apply a similar function to animate the dot as it comes down onto the screen. When both animations happen at once a smooth curve emerges—mathematics is great!

At its core Boom Dots is as easy as that: two tweens, some velocity on tap, and a simple collision detection check. Cool, huh?

That’s all well and good, but there’s only one way to really know if the analysis is correct: to make a game that way. So that’s what I did.

Play the game right now in your browser or watch a short video of it.

I chose the Phaser JavaScript framework for this particular prototype. I’d been reading its documentation and it looked well suited to the task at hand. For example, it has the Easing functions that I wanted to use to get the dots moving smoothly. SpriteKit, to contrast, doesn’t have built-in Easing functions—though of course you could write your own or port some code across if you wanted to do this natively on iOS. I tend to experiment with a variety of frameworks and tools just to keep things interesting.

Phaser is great because it takes care of the dull boilerplate work enabling you to concentrate on the actual game. It uses WebGL or the HTML Canvas depending on what is best for the device it is running on, and also provides some useful shortcuts for loading of assets, managing game states, easily adding physics and lots more. Explosions, for another example, also come for free. I used a small plugin to add the “screen shake” effect. The circle-to-circle collision I talked about earlier is also made even easier using Phaser:

Is the distance between the two centre points less than the sum of the two radiuses?

The prototype took me a few hours from start to finish, with another few the following day balancing, polishing and adding high score saving. I tend to do these reconstructions a few times a year, mostly on Bank Holidays.

The complete source code for my version of Boom Dots is on GitHub.

Of course, Boom Dots goes a lot further than the core simple mechanic. It has a thick layer of presentation varnish. It tracks every bit of gameplay and uses them to give a steady stream of meta challenges to the player. These “missions” encourage the player to approach the game in different ways; to achieve certain goals in the gameplay such as getting a perfect hit, or surviving for a certain amount of time. It also introduces graphical themes that can be unlocked with extended play. These things keep the player in the game and the developer earning money through ads and in-app purchases.

The developer, Sven Magnus, certainly knows how to juice up a game. That’s a topic for another post.