Kenta Cho is a Japanese indie game developer, who has been active since the 1980s. He became well-known in the West in the early 2000s with a series of bullet hell shoot-em-ups. In 2021 he created a total 139 games, which is one hell of a lockdown project. In early 2024 his game Paku Paku went viral, as “1D Pac-Man”, a year after it was made.

I reached out to him with some questions and he was gracious enough to answer them candidly, from one game developer to another.

I’ve been following your work for 20 years at this point, so I’d like to know more about you as a person and a game developer. Can you please share some details about your background and current professional status?

After studying information science at university, I joined a manufacturing company in an IT-related research position. Currently, I work as a manager in system development. I have never worked in the gaming industry.

Wow! You’re a true indie in that you’ve never worked at a game studio! Well, let’s start at the beginning: what was your earliest experience with video games?

It was Nintendo’s Game & Watch. Around that time, I lived in an apartment, and I used to exchange and play various Game & Watch games with my friends who lived there. Titles like Fire, Manhole, Helmet, Parachute, and Octopus were simple yet extremely exciting. The simple gameplay of Game & Watch has become my foundational experience in gaming, significantly influencing the small games I make now.

Also, at that time, game arcades were more adult-oriented, making it difficult for children to visit, so arcade games were objects of longing that I couldn’t actually play. Instead, there were various LSI/FL games (in the West we usually refer to such games as LCD games or handheld electronic games) that ported those arcade games, which I also played with friends. Games like Heiankyo Alien and Frisky Tom, ported to machines with specs far inferior to arcade games, were almost different games, but their core gameplay was well-designed, and I loved playing them. The LSI game version of Pac-Man, released by multiple manufacturers, was interesting because each one had its unique arrangement. It was enlightening to realize that depending on the arrangement, a variety of variations could be created from the base gameplay, which greatly influenced my game development.

- List of Game & Watch games at Wikipedia

- Handheld Games Museum

So even in these early days you were captivated by simple and effective gameplay. Was it at this point that you began programming computers?

I was about ten years old when I saw a TV educational program called マイコン入門 “Mycom Nyumon” (Introduction to Microcomputers). “Mycom” is another name for microcomputer, which was the term used during the dawn of personal computers in Japan. At that time, it was very rare for households to own a personal computer, hence the microcomputer was colloquially called “Mycom”, short for “My-computer”. “Mycom Nyumon” was a program aimed at complete beginners to computers, explaining things like programming. Watching how computers could perform various calculations and control the screen, I thought they were like magical boxes and was utterly fascinated.

Later, my father bought a SHARP PC-1500, a pocket computer, and brought it home. That was my first experience with programming in BASIC, and I thought it had potential unlike any machine I had seen before.

- マイコン入門 (Introduction to Microcomputers) at Wikipedia (Japanese)

- ポケットコンピュータ (Pocket computer) at Wikipedia (Japanese)

- Pocket Computer Manufacturers Database

Despite the limitation of the single line display on those pocket computers they were host to many great games. I can see their influence in your games today. At what point did you decide to create your own game?

The next microcomputer we got was the NEC PC-6001. This was a type that connected to a TV. It was a fresh experience to turn the TV, usually just for watching shows, into something interactive that could be operated with keystrokes and programming. At first, I created games in BASIC, but I was dissatisfied with the processing speed for action games, so I learned to hand-assemble for the Z-80 and began creating games in machine language.

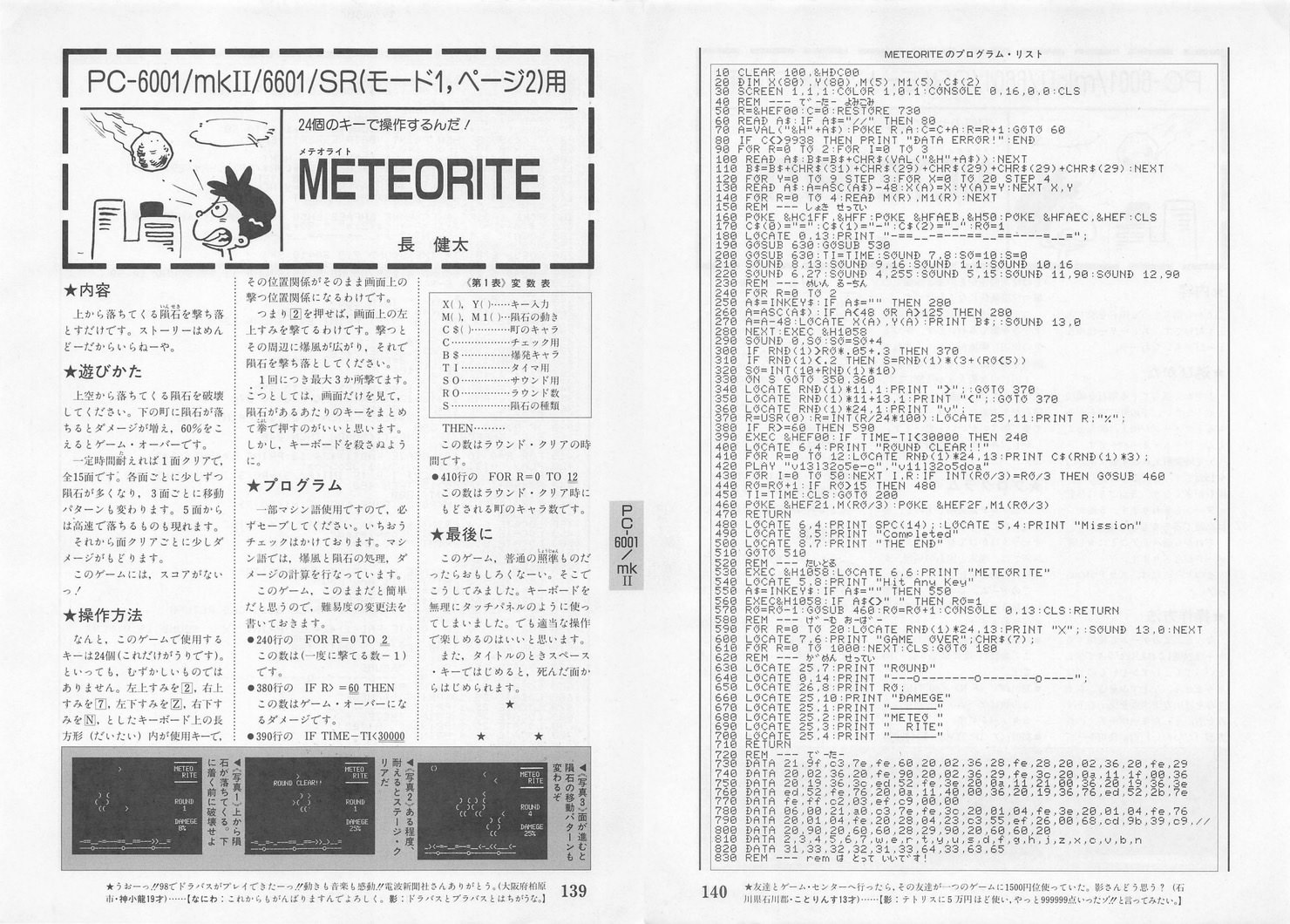

In Japan, there was a magazine called マイコンBASICマガジン “Mycom BASIC Magazine” that accepted submissions of game programs from readers and published them. Each game in the magazine had several pages of source code, which you would enter manually to play the game. These games, despite their compact source code, were full of originality. There were action games about making hamburgers as ordered, race games combined with Pac-Man’s power pellets, puzzle games incorporating rock-paper-scissors, etc. Inspired by how such diverse games could be created depending on the idea, I wanted to make such games too.

I tried submitting some games I made to “Mycom BASIC Magazine”, but it was tough to get them accepted. Only one got published – METEORITE - a game where you shoot down meteors falling from the sky. The game had a unique control where the position of the keys on the keyboard was linked to the attack position on the screen, and you determined the attack location by pressing the keyboard with a clenched fist.

- Mycom BASIC Magazine at Wikipedia (Japanese)

- Mycom BASIC Magazine at Internet Archive

- METEORITE — source code in the 1989-09 issue of Mycom BASIC Magazine

- METEORITE — tape file for use with a PC-6001 emulator

Thanks to Dustin Hubbard (Hubz) at Gaming Alexandria for transforming the magazine source code listing into a tape image. This was done using specialist Japanese software ProgamListOCR and DumpListEditor that are tailor-made for getting old source code off the page and into the computer, so thanks also to the authors of those applications. Video game preservation is a worldwide effort.

Your formative years coincided with the “golden age of video games” period from the late 1970s to the early 1980s. What inspired you at that time?

It was Namco’s arcade games. In the 1980s arcade games, I felt that the ideas in games released by Namco were particularly excellent. Dig Dug’s one-shot reversal reward using rocks and the risk of being crushed by them, Xevious’ beautiful graphics and well-crafted enemy flight curves, Gaplus’ super-fast enemy movements yet fair game balance, and New Rally-X and Bosconian’s combination of all-direction scrolling and radar screens requiring complex situational judgment – Namco kept releasing games with very innovative mechanisms. A lot of my belief in the importance of novel mechanisms in game production comes from encountering Namco’s arcade games during this era.

- List of Namco arcade games at Wikipedia

I apologise for this next question, as it’s almost impossibly difficult, but I’m keen to learn more about you from the games you like to play. So… what are five of your favourite video games, and what aspects make them special to you?

Transport Tycoon — it’s a railway management simulator, released by MicroProse. I also liked its predecessor, Railroad Tycoon, but I played Transport Tycoon for a longer time. A major difference between the two is that in Transport Tycoon, there are rival companies laying tracks on the same map. It was fun to strategize and lay tracks aggressively to important cities to beat rivals. It’s my favorite game in the city development simulation genre. The isometric beautiful graphics and lively BGM (background music) were great too.

Dodonpachi — the first title in CAVE’s famous Dodonpachi series of bullet hell vertical scrolling shooters, following its progenitor, Donpachi. A fun aspect of bullet hell shooters is the technique called “cutback”. It involves rapidly moving the player to one screen edge to create gaps in bullet patterns, then escaping in the opposite direction through these gaps. Dodonpachi’s stage 5 offers the best experience of this, influencing the shooting games I would create later.

Ikaruga — a vertical scrolling shooter with a unique system where both the player and enemy bullets have black and white attributes, and bullets of the same attribute can be absorbed. This system provided a gameplay experience quite different from previous shooters. Although released as an arcade game, perhaps thinking it too different for ordinary players to accept as is, the first stage offered an “infinite lives trial game” mode. At first, I had no idea when to switch attributes and was helplessly defeated many times. But once I understood which enemies to attack with which attribute and when, the game became addictively charming. The chain combo for defeating three enemies of the same attribute in succession and the complex attack patterns of stage 4’s so-called “Rafflesia” added to its depth. The groundbreaking game system offered an artistic playing experience, impressing me with the high potential of gaming.

THE ATLAS — a PC exploration game set during the Age of Discovery, released by ArtDink. Its feature was a procedurally generated coastline, different in each game. The player dispatches a captain from Lisbon to survey coastlines and ports. Upon the captain’s return, you can choose to “believe” or “disbelieve” their report. Disbelieving discards the survey results, but here comes the twist with the procedural generation. If the captain reports an endlessly long, supply-challenged coastline, or a closed one preventing further survey, disbelieving it could generate a more advantageous coastline in the next survey. The game skilfully integrated procedural mechanics with the game system, deeply enlightening me about the benefits of incorporating procedural elements into games.

Rez — a 3D shooter with abstract wireframe graphics and techno music synchronized with sound effects. The immersion provided by this game was unique, supported by the excellence of its visuals and music. Especially, the sound effects being quantized to match the background music’s rhythm and beat, making game operations and actions feel like playing an instrument, was brilliant. I have incorporated a similar quantization mechanism in the games I’m creating now.

I see a nice balance of gameplay systems and skill in all of those games. That brings to mind the types of games you create. Now, if you could have developed any existing game, which one would you choose, and why?

That’s Herzog. It’s a real-time strategy game released by Technosoft for personal computers. Overseas, the sequel Herzog Zwei, which was released for the Sega Mega Drive, is more famous, and the original Herzog might not be as well-known. It’s an action game where you control a robot that can move both in the air and on the ground. The battlefield is a vertically long strip, with enemy and ally bases located at each end. Players could produce units like infantry, tanks, and anti-aircraft guns at these bases and dispatch them towards the opponent’s base. At that time, it was quite rare to have a game where you could produce allies other than the player and fight together. I was very impressed by this game, where you could fight as part of an army against enemy forces.

Later, I even created a game similar to Herzog for the PC-9801. I made the screen 3D and added an arrangement where you could freely board any friendly unit on the battlefield, intending to make the game even more enjoyable.

- Herzog (MSX) longplay on YouTube

In the early 2000s many Western gamers developed a real interest in Japanese indie games, particularly shoot-‘em-ups (shmups). You gained recognition for multiple shmups, and you were even interviewed by MTV! Can you share any experiences from that period?

At that time, I often played bullet hell shooters released by CAVE at game arcades, especially loving Progear no Arashi. Progear’s bullet patterns were very complex compared to earlier CAVE games, like fan-shaped bullets shot in nine directions, slowly decelerating, and then five straight bullets targeting the player. I wanted to replicate such complex bullet movements in a simple way and developed the BulletML language.

With BulletML, I developed Noiz2sa, aiming to achieve the fun of bullet hell dodging with the immersion of games like Rez. In rRootage, I used BulletML for procedural generation of bullet patterns, aiming to create infinite attack patterns. After developing a technology called Bulletsmorph and extensive balancing, I finally released it. It was challenging to achieve patterns that were fair and challenging without reducing variation, but I think it worked out well. Among my shooting games often featuring auto-generated levels, TUMIKI Fighters, where levels were manually designed, was somewhat unique. But this was simply because I found Namco’s Katamari Damacy so enjoyable that I wanted to combine it with a shooting game. Attaching enemies to your ship until it occupies more than half the screen, this kind of shooting game is still quite rare, so I think it turned out to be a game with originality.

Also, during this period, I entered various game contests with my games. Games for the WonderSwan on WonderWitch, games for Xbox 360 on XNA, and games for contests on P/ECE. Fortunately, some games won awards. I had opportunities to present my games to judges, which was enjoyable. Playing my games on these consumer devices was a fresh experience for an amateur developer. Also, optimizing for each device’s characteristics provided many interesting development experiences.

In the following years I continued to follow your work and noticed a move towards the web browser as your platform of choice. More recently, I was wowed by your prolific output, particularly the 139 games you made in 2021! I’m wondering, what motivates you? And can you outline your creative process?

Around 2008, I realized I could make browser-playable games by implementing them in ActionScript3, a programming language for Flash. I knew about Flash, but I thought of it more as a platform for creating animations than games. However, ActionScript3 was a sophisticated language with diverse features, allowing me to create games using just code. Browser games are more accessible than conventional games, so I started making many small action games that could be played intuitively in a short time.

Through this process, I realized that making lots of small games was ideal for trying out various game ideas and mechanics. Since then, I’ve been experimenting with how to make games enjoyable by thinking about mechanisms that haven’t been seen much in previous games and trying to turn them into fun games. This has become my basic process for game development.

Already you’ve mentioned multiple programming languages in this interview. What factors do you consider when selecting programming languages, platforms, and technologies for game development?

I flexibly switch programming languages depending on the target device for the game. For the PC-6001 or MSX, Z-80 assembler; for PC-9801, Borland’s Turbo C; for Windows, Delphi or GCC; for XNA, C#; for browsers, ActionScript3 or JavaScript, and so on.

But I don’t just use commonly used programming languages; I also look for languages that are easier to use and equipped with new technologies. For example, the D language as a replacement for C, offering object orientation without the complexity of C++ and faster build speed; Haxe, superior to ActionScript3 with features like Mixins and Enums; TypeScript for type-checking JavaScript, allowing proper error detection and code recommendations. I actively use them even if they are slightly less mature or have weaker ecosystems than traditional languages if they can improve development speed.

I really appreciate how technology agnostic you are. It’s noticeable that the game is the number one priority and the choice of technologies is not so important. This is similar to how I work, in that I’m happiest when the technologies fade away and I can concentrate on the game design and implementation details. Could you tell us more about your approach to game development?

As I mentioned earlier, I think about game mechanisms that haven’t been seen in previous games. However, it’s challenging to conceive completely new mechanisms. Instead, I often borrow and arrange parts of mechanisms from old arcade games or submission magazines like “Mycom BASIC Magazine”. Old games focused more on the novelty of rules and mechanics than on content like scenarios, which is very informative for game development.

I also create games driven by specific technologies. I’ve incorporated procedural content generation and physics calculations into shooting games. Before Windows, I implemented 3D drawing logic and software-based screen rotation, scaling, and shrinking. Recently, I’ve been experimenting with whether everything from game idea conception to programming can be procedurally generated.

I’m also interested in this aspect of game development, it’s a deep well with a lot of opportunity. I can see its influence in many of the games you’ve created using your Crisp Game Lib. What was the thinking behind your framework?

The goal of Crisp Game Lib is to enable the creation of innovative games within a three-hour timeframe. For this, I made it easy to implement collision detection, which is typically challenging. I particularly focused on making collision detection easy for geometric shapes like lines and arcs, allowing the inclusion of geometric shapes as terrain, obstacles, players, and enemies. This makes it easier to create games different from traditional sprite-based 2D games.

It also includes features for procedurally generating background music and sound effects. Automatically generated background music and quantized sound effects make it possible to create enjoyable games even within a short development period.

Your recent games use quite simple scoring systems, especially when compared with arcade or pinball scoring systems. What are your thoughts on scoring?

In a simple scoring system, it’s important to reward the player’s risky actions with high scores. Assigning high scores or multipliers for actions like attracting and defeating many enemies at once, narrowly avoiding enemy attacks, or collecting hard-to-reach items can add depth to the gameplay. Additionally, I make it a point to clearly display the acquired score and multipliers on the screen, making it easy for players to understand how to earn high scores.

The gameplay concepts in your recent games are also beautiful in their simplicity, but at the same time they have depth. How do you approach the difficulty curve to ensure your game is enjoyable for as many people as possible?

I often use the traditional Game & Watch era mechanic of increasing difficulty as time goes on from the start of the game. In such cases, I consciously choose between a linearly increasing difficulty (difficulty = time) and one that gradually becomes milder, using the square root function (difficulty = sqrt(time)). Linear is usually fine, but for parameters like enemy size, which could become unreasonably difficult if too large, I use square root to maintain game balance over time.

As mentioned in the previous answer, rewarding risky actions is closely related to appropriate difficulty settings. Increasing difficulty over time means to achieve high scores, players need to take risky actions and score high from the early, easier parts of the game. This avoids boredom in the early stages, making the game enjoyable from the start.

In January 2024, your game Paku Paku went viral after being featured on Hacker News. It was picked up by various bloggers and news outlets, and was even ported by fans to multiple systems. Were you surprised by this turn of events, and why do you think the game garnered such attention?

When I released Paku Paku a year ago, it was fairly well-received among Japanese players, but I was surprised that it gained attention from international players a year later. Many articles described Paku Paku as a ‘1D Pac-Man’, which likely sparked curiosity about how a 1D version of Pac-Man could be realized. Paku Paku was an example of the demakes and minimalization I often do when making small games. Successfully balancing it as a good game within the strong constraint of 1D might be why it became popular. My experiences with games I made and played during the pocket computer era were very helpful in developing a 1D game.

- Play Paku Paku in your browser “…just one more go…”

Originally published: 2024-02-10

--

Enjoyed this blog post? Please show your support.

--

Comments: @gingerbeardman